Against a background of global climate change, healthier cities and communities are shaped by taking tough decisions on issues such as air quality, resilience planning, spatial strategies, working practices, active travel, sustainable homes and green spaces. How can we design a thriving, health-inducing future for all citizens – and avoid a dystopian alternative where our cities descend into crisis and chaos?

Making our cities more healthy, successful and sustainable for people to live, work and play in requires a co-ordinated interdisciplinary effort across a wide range of areas – from policymaking and governance to investment, planning and design. Progress in one area can be slowed or impaired by a lack of action or resolve in another.

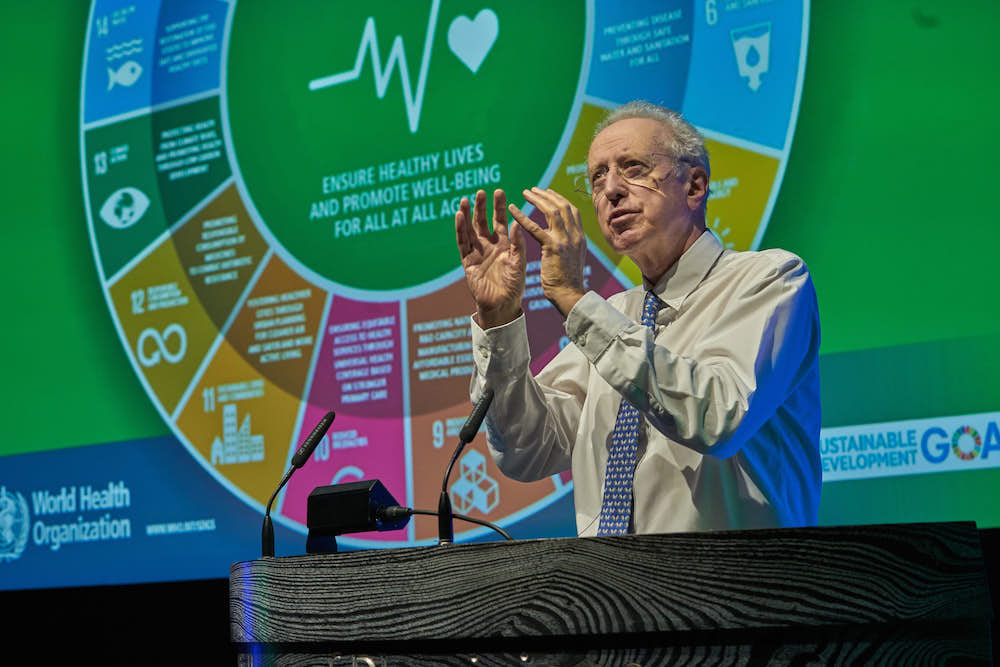

As a result, the bigger picture around improving the health and sustainable development of our cities can be challenging and often overwhelming. Are we moving in the right direction or doing things now that will make matters worse down the line for both people and planetary health? How do we reconcile economic prosperity with the preservation of the natural planetary systems that sustain life? As Dr Howard Frumkin, head of the Our Planet, Our Health programme at the Wellcome Trust told the Healthy City Design Congress in 2018, we should not be “mortgaging the health of future generations for economic growth in the present”.

The movement to develop healthier cities appears to be coming to a crossroads. On one hand, there is a utopian vision of urban change and renewal, with the green shoots of revival clearly evident in a host of policies and projects that support healthier lifestyles. In this scenario, walking, cycling and public transport addresses over-reliance on the car; effective resilience planning stops the spread of infectious diseases and mitigates the effects of climate change; exible working strategies and environments reduce stress and improve productivity; and access to safe, affordable housing, green spaces and healthy local food underscore a commitment to community wellbeing. Technological advances and AI are safely integrated into our daily lives, enhancing city services, increasing efficiencies and creating intelligent environments, seamlessly converging with art and culture in the city to improve the quality of life for all citizens in a fair and equitable way. As a result, a significant burden is lifted off formal healthcare services.

The alternative vision is dystopian. In this scenario, indoor and outdoor air quality (already unacceptable in many cities, homes and workplaces) deteriorates further as cars clog up the roads; more than 500 cities are threatened with flooding and many more with water shortages and heatwaves more intense than ever before; tensions rise between well-heeled business districts and areas of urban deprivation that circle them; ‘food deserts’ increase and green spaces are gobbled up by development. Healthcare services, in this scenario, start to collapse under exceptional pressure and demand.

In this, our third Healthy City Design International Congress, we’ll address the question of designing for utopia or dystopia. In a world where the effects of population migration and ageing play out amid rapid urbanisation, how can we support cities to take a healthier path? How can we ensure that, despite the best intentions of policymakers, urban planners, public health professionals, architects, designers and developers, our worst dystopian nightmares don’t come true. Environmentalist Sir David Attenborough’s impassioned plea to save our planet at the World Economic Forum in Davos, in January this year, effectively sketched out the destructive path we’re currently on.

The inaugural Healthy City Design Congress in 2017 explored ways to bring public health and urban planning professionals back closer together after a long period of drift and divergence. Our second congress last year focused on the need to address health inequalities in cities by designing for equity and resilience. In essence, the first reinstated a basic principle to develop healthier cities; the second raised the bar in terms of ambition. In our third congress, we will build on both of these themes to look at alternative futures for healthy cities from several angles.

We’re delighted to invite you to contribute and participate in the exchange of knowledge on the design of our future cities at this critical juncture for their development. We welcome abstracts addressing a diversity of issues within low, middle and high-income countries, and from across the disciplinary spectrum at the intersection of research, practice and policy. Various formats, from the presentation of themed papers and posters to more interactive ideas for workshops are encouraged and should be submitted by the extended deadline of 29 May 2019 at www.healthycitydesign.global.

We also recommend viewing videos of talks from previous congresses in the Talks section of our online community and journal at www.salus.global/journal.